When I meet Om Dhungel in a cafe near his home, he tells me about Merryn Howell. “She is my godmother,” he says, his eyes shining. “Every day I remember her.”

Howell (then Jones) was a skilled migrant placement officer. Dhungel was a refugee of Nepalese ancestry from the Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan, where he had been an engineer and a senior public servant at the Department of Telecommunications.

In 2001, after three years in Australia, Dhungel completed an MBA. But over the next six months, he applied for 52 jobs in engineering and business administration, and received 52 rejections.

Om Dhungel in his home in Blacktown, Western Sydney

People, offering sympathy, told him the problem was racism, or the fact that he was a refugee. Dhungel began to despair: the job he had packing shelves at Coles would be his for ever. But Howell refused to believe any of that. Keep going, she insisted. You will get there.

After the 52nd rejection, she had an idea. She would conduct a mock job interview with Dhungel, and film it.

“I came in the next day and she was jumping up and down,” Dhungel says. “She said, ‘Om, I’ve got it! You are looking down at my feet. Look at my face!’”

Dhungel had simply been observing Bhutanese custom, which sees looking directly at a person of higher rank as a mark of great disrespect. Confident now that his problem wasn’t racism or being a refugee, Dhungel returned to the search.

In no time he had two good job offers, the second an engineering-related role at Telstra. He stayed at the company for 10 years. He says he will use the lesson Howell gave him for the rest of his life.

‘I’m a Blacktown boy’

Blacktown has traditionally been a working-class community. In the early decades after the second world war, many waves of migrants from other parts of Sydney and the world came to an area that was rich in jobs in small factories, warehouses, building sites, and service centres such as Blacktown hospital.

As a growing city deeply divided by socio-economic status, Blacktown depends on its people to hold it together

But Blacktown is changing more than any other time since that postwar period. Although its south and west – especially the 11 suburbs of Mount Druitt – hold some of Australia’s poorest urban areas, its northern suburbs and the greenfield developments of the North West Growth Area are at the centre of a housing boom that is creating some of Sydney’s most affluent new areas.

Unemployment is rising, especially among young people, yet in the past 50 years there has been huge growth in the proportion of Blacktown residents holding tertiary degrees – from well under 1% in 1971 to nearly 17% today.

As a growing city deeply divided by socio-economic status, Blacktown depends on its people to hold it together. People like Dhungel.

A small, finely built man, nearly 60, Dhungel runs his own consulting and mentoring practice. He sits on multicultural advisory committees with Blacktown city council and NSW police, and on the board of the Asylum Seeker Centre. He was chair of SydWest Multicultural Services in Blacktown, and lives in an elegant but not exclusive estate near the Blacktown CBD.

“I’m a Blacktown boy,” he says with a laugh, and with pride.

He was once a boy from Bhutan, from an ethnic Nepalese background. His family lived in a village in the south of the Himalayan kingdom. His parents, Durga and Damanta, ran a grocery at the market, but their son was educated well, and rose into the high ranks of the public service. He had conversations with the king, making sure to keep his eyes down when he did.

People of Nepalese ethnicity had lived in Bhutan in large numbers for more than 100 years. But many ethnic Bhutanese thought their numbers were growing too fast, and feared being overtaken. A movement grew: One Nation, One People. The ethnic Nepalese were prohibited from teaching their own language. From the late 1980s, the regime began a campaign to expel them. Durga was accused of supporting insurgents, arrested and tortured till he passed out. When the family left, they lost everything.

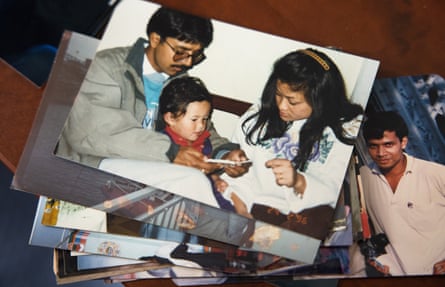

Family photos of Om Dhungel and his wife, Saroja

By 1996, there were 100,000 Nepalese-Bhutanese refugees in camps in Nepal. Dhungel, his wife, Saroja, and young daughter, Smriti, lived in the capital, Kathmandu, so that he could advocate to the Nepalese and international governments on behalf of the refugees. While Saroja taught science in a local school, Dhungel worked as a full-time but unpaid human rights activist, and co-edited a newspaper, The Bhutan Review, that sought to draw the world’s attention to the plight of his people. He and colleagues delivered it by walking to every embassy in Kathmandu; Dhungel often carrying Smriti on his back as he travelled.

Those six years in exile, in which he learned to live with virtually nothing, were the most important and formative of his life.

The camps that housed the Bhutanese were poor but, unlike those in Kenya and Ethiopia that housed many South Sudanese, they were in the main not violent. There were divisions and some of these were bitter: some people wanted to take up arms to try to regain their land in Bhutan; others said they had to renounce that dream.

Most agreed on two things: they would continue to press for their return to Bhutan, and they would do everything to educate their children. They opened schools under palm trees, and they waited.

Hemanta Acharya was one of those children, and remembers her hunger to learn. In the camp where she spent the first 15 years of her life, her parents would tell her: “It is time to go to sleep, you don’t have to study so hard.” There was malaria in the camps and Hemanta’s friend died of typhoid. Her father had been a respected educator and community leader in Bhutan, for which he had been imprisoned for 15 months. But Hemanta wanted to be a doctor or a nurse, to prevent the kinds of needless deaths she saw sometimes in the camp. And she would watch aeroplanes making their way lazily across the sky and think. “One day, if I’m lucky, I will be on that plane.”

‘I feel a sense of gratitude to where I came from. It keeps me humble,’ Hemanta Acharya says

She already felt lucky, though. The camp’s houses were made of mud, the roofs of bamboo and thatch. Rain would get into the houses and pool on the floor. “We didn’t care,” Hemanta says. “Cousins, neighbours – we all grew up together. We were so happy with what we had. We had dance competitions, quizzes, debates. We didn’t know iPhones, laptops, the developed version of life.”

In the late 2000s the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees embarked on a concerted effort to clear the camps with the help of eight western nations. Australia agreed to take 5,500 of the 100,000 refugees. In 2008, Dhungel had been in Sydney for 10 years. The Australian Bhutanese community he belonged to numbered precisely 17 people. To prepare for the newcomers, Dhungel and others formed the Association of Bhutanese in Australia (ABA).

Celebrating successes – big and small

When Hemanta finally learned that she and her family were going to Australia, she counted every day till departure. As she boarded the flight, she said to herself: “Let this be the last day I am a refugee. As I land on Australian soil, let my refugee tale stay inside the plane.”

When the family and others landed in Sydney, Om Dhungel, his wife, Saroja, and other members of the tiny Bhutanese community were waiting at the airport. Most people were taken to townhouses in Blacktown. Om and Saroja showed them how to work the lights and the flush toilets, how not to get burned by the hot tap or trigger the smoke alarm. Learning how to use a stove would take longer, so Om and Saroja gave about 50 families rice cookers. They also left food, especially vegetables such as chokos and rayo saag, a spinach that grows in Bhutan, in the fridge.

In that first week, as the family of nine children, parents and grandparents shared three bedrooms, Hemanta would lie awake, wanting to start school but wondering, given her broken English, how she would go. Entering Year 9 at Mitchell high school, she struggled to pronounce “shower” and “sour” differently, but she made friends quickly, even if Jenny, an Anglo name, sounded like Zenny, a Filipino name.

Om Dhungel and his wife, Saroja, looking at old photos of their time in Nepal, where Om worked full-time as an unpaid human rights activist

Following her older brother, she took up soccer. On Saturday mornings, Om Dhungel would pick up a group of girls in his car and drive them to training. In the camp, kids had played with a ball made of socks and plastic, but girls were not welcomed. Now Hemanta found she had a gift for the game. Her progress was swift, and in June 2010, she represented Australia in the Fifa Football for Hope festival for refugee youth, held during the 2010 World Cup in South Africa. She had been living in her new country for about 18 months.

Hemanta’s journey was part of what many government officials regard as the most successful refugee integration program Australia has ever undertaken. Critically, it was not run by external service providers alone but with the close involvement of the Bhutanese community.

As people continued to arrive, the ABA developed a plan to identify their skills and put them to use. Many had never been to formal school, and could not read Nepali. In partnership with an employment services provider, MTC Australia, the ABA created a spoken English school in Blacktown, run by community volunteers. Young Bhutanese were engaged to cut hair, do basic repair of computers and phones, or fix a tap. Others ran workshops on résumé writing and interview skills. A group was organised to take part in Blacktown’s Clean Up Australia Day, to “showcase our sincerity and commitment to the nation”.

For many people, especially women, gaining a driving licence was the key to independence. Three women, including Hemanta’s mother, set up childcare centres, an opportunity that would not have come their way in Bhutan. Every Friday, the community held a seniors’ get-together with a yoga class at SydWest Multicultural Services in Blacktown.

Members of Blacktown’s Bhutanese community gather together after being separated by the pandemic for months

All these efforts came together in a monthly event held in a hall in Blacktown. The council provided the hall rent-free for 18 months, until the ABA offered to pay its own way. Jill Gillespie remembers people being brought up on stage to share an achievement. One would hold up a Year 11 certificate, another an L plate, to great applause. Gillespie says “these successes, however little they might seem in the broader sense of life, were all celebrated”.

Gillespie says “the amount of time Om gave to the community in those early days was beyond my comprehension. He had a full-time job at Telstra!” She thinks the Bhutanese leaders “were smart cookies. They could see the value of early intervention to minimise problems down the track.”

There were episodes of domestic violence and depression. Some people struggled to learn English or find jobs; others regretted a lack of contact with the wider Australian community. Nevertheless, a survey from 2019 showed that very few people who were eligible to work or learn were not doing so. More than 60% of families owned their homes. Those who couldn’t afford to buy left Sydney for more affordable places such as Adelaide, the largest Bhutanese centre, and Albury-Wodonga. In 2015, then home affairs minister Peter Dutton singled out the Bhutanese for “supporting each other to quickly gain employment and independent living”.

‘They don’t need charity, they need inspiration’

Over time, Dhungel has come to feel that Australian policy towards refugees is discouraging that opportunity for independence. He says that settlement services, by being run as a form of social welfare, are not nurturing the strengths of individuals or of their community.

Under the current model, large providers compete for lucrative government contracts to deliver services to refugees. The more contracts a provider wins, the more it grows. To deliver the contract, it hires lots of specialist staff. Dhungel says these employees, often young and well-meaning, are required to undertake a “needs analysis” of the community, then to develop programs based on those perceived needs. Providers are not even required to engage with communities, simply to deliver the service.

Main Street, Blacktown. The community is ‘definitely coming together’, Om Dhungel says

Dhungel says providers are not acting in bad faith; they have to meet government funding requirements and other performance indicators. Yet he says their focus on refugees’ perceived weaknesses and needs, rather than their strengths, is breeding a culture of dependency. And by not engaging with communities, they are spending resources on tasks that communities could do themselves, learning valuable skills along the way.

This is one man’s view, yet it is not a lone one. Hazara, Khmer and South Sudanese organisations all testified to the Senate’s Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee that the move from a community-based funding model to one dominated by large service providers had been damaging. The NSW Service for the Treatment and Rehabilitation of Torture and Trauma Survivors, which works with many communities, told the inquiry that some activities “are much better run by refugee organisations themselves”.

Even the constant use of the term “refugee” to denote need frustrates Dhungel. “The sector champions its work with the most vulnerable but refugees are not vulnerable. They have often lived for long times without food, or divided one mango between two families. The service sector could strengthen communities by helping to build an array of champions within them, then step back to let communities do things by themselves. They don’t need charity, they need inspiration.”

Dhungel believes the possibility of inspiration is abundant in Australia. Flick a switch, and the light comes on. If a road gets a pothole it is paved. People died in the Snowy Mountains so others could have power. His father, Durga, whose experience of torture made him fear people in uniforms, went on a tour of Blacktown police station. The commander, Mark Wright, invited him to sit in his chair. Sometimes Dhungel cannot believe the blessings of this country.

‘It’s a good problem to have’

I ask him whether he thinks Blacktown is coming together or apart as a community. “Based on my experience, I think it’s definitely coming together,” he says.

His evidence? This year, Blacktown mosque invited about 30 non-Muslim leaders to the iftar to celebrate Eid, the end of Ramadan. Community festivals increasingly involve people from other groups.

And earlier this year, a group of 10 Bhutanese of different ages got together to discuss how their community was going. A few lamented that the common bond they felt when they arrived in Australia had gone. People were working, studying and staying in their own friendship groups; fewer came to community events, that first rapture had been lost. One person asked: “How do we get back to 2008?”

But other people replied: the reason our Bhutanese gatherings are smaller is that people are socialising in the wider community. They play sport with other Australians. Many Bhutanese – more males than females – are nurses, and they are having drinks, joining Facebook groups with workmates, and buying homes. One person said: “This is such a good problem to have.”

I say to Dhungel that maintaining such cohesion relies on forces that are bigger than the Bhutanese: above all, the strength of the economy, the guarantee of getting a job. He is reluctant to entirely allow the point. “There is always something you can do,” he says. “What can we as a community do? We can’t always rely on the government to help us.”

He has put that idea into practice. During the pandemic, SydWest Multicultural Services in Blacktown brought together a group of leaders from Bhutanese, South Sudanese, Sri Lankan, Indian, Sierra Leone and Afghan backgrounds to discuss what they could do together to combat isolation and loneliness in their communities.

That group turned into a community leaders Covid-19 taskforce, hosted by SydWest, that met every month on zoom. When 12 local government areas in Sydney’s western and south-western suburbs were subjected to especially severe restrictions during this year’s lockdown, the taskforce began to meet on zoom every fortnight, and to discuss how communities could work together to get their people vaccinated.

Forum members came up with the idea of virtual doorknocks: a volunteer would contact 10 people and ask each to contact another 10, to encourage community members to take the vaccine. These volunteers would also try to clear up misunderstandings – for example, the presence of soldiers, helicopters and more police in the area did not spell political trouble but that the government was trying to ensure people’s health and safety.

Government figures from the start of November show that Blacktown’s double-dose vaccination rate of 94.8% was the highest among the 12 “LGAs of concern” and was beaten by only five other LGAs across the state. Such success is unlikely to have occurred without the “community champions” that Dhungel and others created, and without his insistence that “there is always something you can do”.

Hemanta Acharya with her grandmother, Menuka Devi Acharya, and her aunt, Devi Maya Acharya

Hemanta Acharya has worked as a registered nurse for the past five years and recently completed a Master of Nursing. She looks forward to the opportunities her degree is likely to bring. She also does media interviews for the community, writes for a Bhutanese literature blog and runs an occasional dance academy. She was the youth coordinator of the ABA in Sydney and is one of the community’s most active members.

In a cafe overlooking a golf course in the Blacktown suburb of Colebee, she reflects on what she has lost and found in coming to Australia. She admits she feels nostalgia for aspects of the life she had in the camp. “I don’t miss the leaking roof, I miss the human connection. Now we are complaining about this flood [we spoke during a serious flood in Sydney]. It hasn’t even gotten into our houses and we complain. We are on our phones even when we are eating at home. My brother will be watching a football match, I will be watching a dance show, Dad will be watching something in Nepalese. In the camp we were together. My mum would leave us with our neighbours or relatives, we had that trust. They would feed us. That human connection is hard to see when you have everything.”

On the other hand, Hemanta knows that if she were still in Nepal she would be a housewife. Even if she were allowed to study, she would have to rely on her husband. Here she has a car, and can go wherever she wants, pursue whatever path she wants. “I feel a sense of gratitude to where I came from. It keeps me humble.”

She says that from an early age, watching planes in the sky from that house with water on the floor, she wrote down her dreams and goals. “There is nothing wrong with dreaming, the biggest you want to achieve. Even if you think you can’t achieve it, always dare to dream. The rules change, the opportunities come along – if you keep that dream alive, one day you will get to a point where you say, ‘Ah, it is already fulfilled.’”

This article is based on a narrative paper on Blacktown written for the Scanlon Foundation Research Institute.